The Identification of American and Pacific Golden Plovers |

CUTTING TO THE CHASE: for readers who just want to know the conclusions, please skip through this page reading only the paragraphs in maroon! |

Comments from Peter Pyle to Greg Niese on October 07, 2011 concerning a juvenile Golden Plover in Illinois: "... Primary extension seems intermediate so could indicate either species [note: Pyle informed me that this was based on seeing a PAGP photo from Washington that he had thought was of the Illinois bird]. BTW I look at wing-tip-to-tail-tip more than relying on tertials or number of visible primary tips. The longest tertial can be in molt at almost any time, throwing this off, and the number of visible primary tips also depends on whether or not p10 is visible, as one of your commenters mentioned. There may be something to this - p10 visible in AMGP and not always in PAGP - but it requires more study and good images to assess this in the field... I do worry about hybrids in these, though, as they were not ruled out at all in Connors' original paper (1983) splitting them (he just found indirect evidence of assortative mating) and the Johnsons have seen birds they were convinced were hybrids [Wally Johnson informed me that this was a miscommunication with Pyle and that the Johnsons have never seen birds that they were convinced were hybrids]. I worry that juvenile hybrids will more likely show up in California and elsewhere between the normal migratory paths of each... Peter"

Oscar and Pat Johnson, in Johnson, O. W, and Johnson, P.M. 2004 Morphometric features of Pacific and American Golden-Plovers with comments on field identification Wader Study Group Bull. 103: 42-49 closed their extensive study and analysis of this ID challenge with the following: "Finally, our best advice to birders trying to interpret a questionable plover in non-breeding plumage is to concentrate mostly on its primary tip exposure and primary projection characteristics. Recognize also... that despite the best efforts of dedicated observers to confirm extralimital records of these plovers, some of the latter will be impossible to identify with certainty."

The above two quotes summarize succinctly the current state of American (henceforth dominica) and Pacific (fulva) Golden Plover identification: Despite lots of effort and published words listing aspects such as bill to eye ratios, bill to exposed tibia ratios, patterns of various upperpart feathers, gestalt of overall appearance, we are down to two or three (actually maybe only one!) features that work. All the other previously-mentioned features are either too variable and overlapping when a decent sample is used, or are too subjective and dependant on posture and environment to be applied consistently.

NOTE: This page is focused on structural features. Plumage features/aspects are not discussed, however I will say that based on my experience and examination of many photographs, and discussions with other birders, a Golden Plover in spring (actually any age except juvenile) that has obvious buffy-golden coloration on the face is (almost) sure to be fulva, assuming no contradictory other features.

About the Conventional Wisdom that most fulvas remain on the wintering grounds for their first Summer. I have no reason to doubt that this is true for 2CY fulvas in their normal range (where they find themselves among many other 2CYs doing the same thing). However I propose that a vagrant fulva that ended-up wintering in Argentina among many dominicas would be under strong pressure to behave exactly as all of the 2CY dominicas - i.e. fatten-up and head north with the adult dominicas. Thus while 2CY fulvas are scarce on migration and on the breeding grounds in their normal range, they should be expected - as a rare vagrant - on north-bound migration and on the dominica breeding grounds in North America.

I'll make a short comment about hybrids: Pyle feels that hybridization between these two taxa is occuring a lot more frequently than all of us would like! The two taxa breed virtually side-by-side (but in slightly different habitats) in western Alaska, yet it would take some extensive research at the breeding grounds to attempt to quantify this. I do not know of any published data on this precise topic, so this matter is limited to speculation. I agree with Pyle when he suggests that if juvenile hybrids are occuring, they may migrate south along a line intermediate between that of Alaskan dominicas and fulvas - and thus are more-likely to occur to the east, among migrating dominicas. One could even ask a more-provocative question and wonder if the fulvas wintering in California really are pure fulva!

Firstly let's address Primary Projection and its limitations. Most authors who quote this feature as something useful - reliable, even - provide a caveat that it cannot be used when the primaries and/or tertials might still be growing, and must be used with caution if the primary tips cannot be assessed properly due to wear/distance or the tertials might be significantly worn and reduced in length. Note that for both taxa tertials are usually molted as part of the Preformative, First Prealternate, Definitive Prealternate and Definitive Prebasic molts and the timing of these molts is individually variable, thus the longest tertial could be in molt at almost any time of the non-breeding period in any age group, and can still be growing during migration (per Peter Pyle).

I would add to this that the actual exposed primary count break point (3-or-less vs 4-or-more tips) is unreliable! Take a look at the following links that show apparent dominicas with only three visible primaries beyond the tertials. NOTE that these were all seen among a 1000+ flock of Golden Plovers in the Texas Coastal Plain in early Spring, in which one obvious fulva was documented, and at least one other possible fulva was present - it is possible that some of these examples are not dominica (but I personally doubt it)...:

EXAMPLE ONE.

EXAMPLE TWO.

EXAMPLE THREE.

EXAMPLE FOUR.

- and I have also seen at least two more otherwise typical dominicas in different years that had only three P-tips visible.

UPDATE: Wally Johnson contacted me and provided a copy of a recent paper he co-authored (Jukema, J. Johnson, O. W. Aldabe, J. Rocca, P. 2011 Wing and tail moult of American Golden-Plovers Pluvialis dominica on wintering grounds in Uruguay, with confirmation that juveniles replace all primaries during their first non-breeding season; Wader Study Group Bull. 118(2); 129-131) in which it was established that 1CY/2CY dominicas replace all of their primaries on the wintering grounds (as do adults), but the timing is somewhat behind that of adults, and it is possible that some 2CY dominicas may be seen on migration in North America with the outermost primaries not yet fully-grown. If this does occur it could account for some (but not all?) of the instances of dominicas showing only 3 P-tips beyond the tertials.

In Summary: for Fall juveniles I consider Primary Projection to be virtually useless because any juvenile might have tertials (and/or outermost primaries) that are not fully-grown to some degree. For spring birds it seems that some dominicas can have only 3 P-tips visible, and with enough data I expect to find photos of fulvas with a fourth P-tip peeking out just beyond the longest tertial, so despite being a good indicator it can only be relied-upon at the extreme (and thus barely useful) ends: 2 or 5 exposed P-tips. |

Next let's discuss tertial-tip to tail-tip ratio: This potential feature has gained some favor in recent years. Again Johnson and Johnson 2004 provides a good explanation: "For fulva: tertials extend to the distal third of tail; (they) end at or near tail tip in most birds. For dominica: variable, from half to distal third of tail". While this may hold true for a majority of birds and in particular for Spring fulvas, I've seen a handful of Spring dominicas with tertials almost or actually reaching the tail tip. CLICK HERE and CLICK HERE to see two examples. NOTE that both of these birds were clearly more-advanced in their overall molt into Alternate plumage - a feature strongly associated with fulva - but both have such long primary extensions that they surely must be dominicas.

In Summary: A Golden Plover with fully-grown tertials not extending into the distal third of the tail should be a dominica, assuming no contradictory features. A Golden Plover with tertials extending into (or well beyond) the distal third of the tail could be either taxon - although if the tertials reach or almost-reach the tail tip this is more typical of fulva.

|

So this leaves just...

PRIMARY EXTENSION (wing-tip to tail-tip):

Johnson and Johnson 2004 estimated primary extension (beyond tail tip) or PE, based on comparing this feature to the average bill length (24.3mm (n=441 for fulva, 22.8mm (n=45) for dominica) and therein quoted fairly precise primary extension values (0-9mm (n=50) for fulva, 12-22mm (n=34) for dominica).

Peter Pyle, in

Pyle, P. 2008 Identification Guide to North American Birds, Part I. Slate Creek Press, Point Reyes, California measured PE from 50 specimens for each taxa (25 1st-years; 25 2nd+ years) and arrived at similar values to those of Johnson and Johnson 2004 (-1-11mm for fulva, 10-22mm for dominica).

I confess to being surprised at the conformity of these two sets of data, given the very different derivation. For his data Pyle states " Note that this value may be the most affected by variation in specimen preparation (Fig 383)". Pyle tells me that he did exclude from his sample a few specimens that were prepared in such a manner that the desired measurement would be clearly inaccurate. I'd go further than his caveat and note that I've seen wild differences in this value for other prepared shorebird specimens (e.g. snipe), and remain very cautious of Pyle's data, despite its correlation with that of Johnson and Johnson.

These two sets of data for PE create a break-point of 10 -11mm. I am unconvinced as to how accurate/useful this is for the separation of these two taxa in the field.

My first concern is over the accuracy of assessing a value from live, unrestrained birds:-

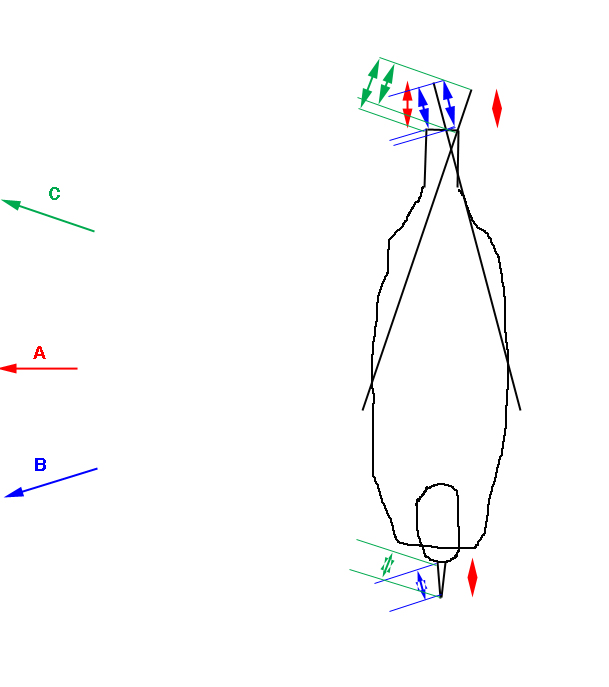

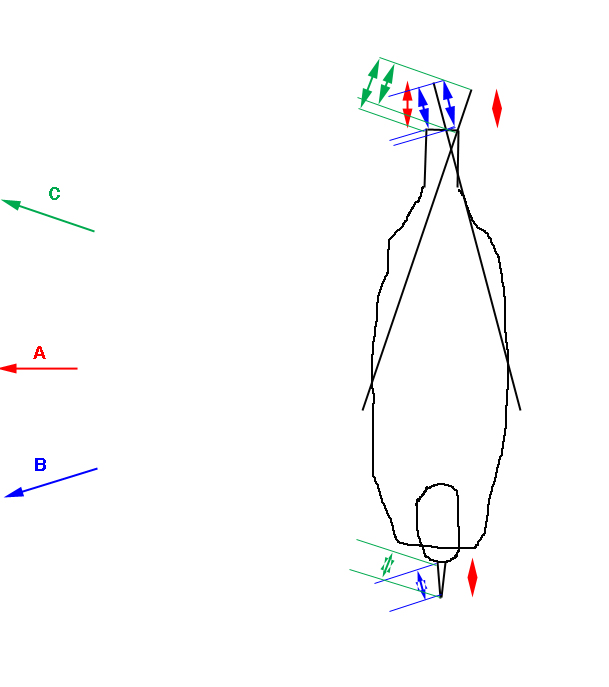

Except on the shortest-winged fulva, for both taxa the wing-tips cross each other over the folded tail, the wings forming a stretched "X" with the basal part much larger than the distal part:

However, it is important to understand that the top part of the "X" - let's call it the distal "V" of the crossed wings - is ASYMMETRICAL. In other words, the angle of one wing-tip (compared to the perpendicular line through the length of the bird) is consistently shallower than that of the other wing-tip. The asymmetry is determined by which wing is on top: in the following crude line drawing, the bird's right wing (= left side of the distal "V" shown here) is on top of the bird's right wing. For the upper wing (whether right or left) it is the folded wing's natural position, and the lower wing would also adopt a mirror-image of the upper wing EXCEPT that the tactile resistance of the top wing and the tail prevents it from achieving the mirror image angle. Put another way: compared to a perpendicular line through the length of the bird, the lower wing will always be at a shallower angle (and thus appear longer) than the top wing.

Think of it this way: the lower wing will always extend a little further than the upper wing beyond the tail tip. Another way that this asymmetry is expressed is the amount of upper tail area that is visible on each side; look again at the illustration above, and you can see that there is more of the tail visible from the side when looking from the bird's right side - i.e. when looking from the side where the nearest wing-tip to the observer is the lower wing. Here is an example on an actual bird:

View A: compared to the line drawing above, this is like the view from the bird's right (= from left side of illustration) - note the extensive amount of upper tail visible in the photo, as in the drawing:

View B):

compared to the line drawing above, this is like the view from the bird's left (= from right side of illustration) - note the limited amount of upper tail visible in the photo, as in the drawing:

- you can see the same effect from behind in the first photo at the top of this section, above the line drawing.

So, when trying to assess PE we are faced with trying to assess a linear (two-dimensional)

value from a three-dimensional shape. This inevitably means that the ANGLE of view becomes critical to this assessment. When viewing an object the size and shape of a Golden Plover from the kinds of distance normally involved, it is extremely hard to be sure that you are exactly perpendicular to the bird.

Looking at the diagram below (ignore the head/bill for now), let's first assume that we have managed to be exactly perpendicular to the bird (somwhere off in the distance along the red line, A). Already we are faced with two values: the shorter value based on the upper wing-tip (farther red double-arrow), and the longer value based on the lower wing-tip (closer red double-arrow):

Now let's assume that we are slightly off from perpendicular (in most situations we would not be able to detect this) in that the bird is angled with the tail slightly closer than the head - effectively this is the same as if we were standing slightly to the rear of the bird, somewhere in the distance along the green line, C). Again we are faced with two values; now the two wing-tips have got relatively closer to each other but the tail "tip" is no longer a single point but instead a "bar" of potential measuring points.

If we change our position to be slightly ahead of the bird (blue line B) the wing-tips will have gotten further apart, relatively, plus the tail "tip" is again ambiguous.

Another factor that could affect our preceived view of the PE is how tightly or loosely the wings are being held over the back/tail. Looking at the illustration above, it is easy to imagine that any particular bird might be holding its wings more-tightly (forcing them father apart and to more of an angle compared to the perpendicular) and thus appearing slightly shorter-winged than the illustrated bird. An individual with wings held more-loosely could have the tips closer together and thus look longer-winged than the illustrated bird.

Putting together all these elements of assessing PE, it seems clear that for any one bird we might assess the PE to be significantly longer or shorter depending on: variations in the precise angle of view; whether the upper wing is pointing towards or away from us; variations in the tightness of the folded wings. Keep in mind that all this is affecting our assessment of a single measurement without comparison to other features.

This is only part of the problem, because we need to compare the PE to bill length (bill tip to start of feathering of maxilla). Look back at the above diagram and consider the bill length: again to assess it accurately we need to be perpendicular to it. In order to make this direct comparison with the PE, the bird must have its head in-line with its body. The red double-arrows show the correct length when the head is perpendicular to the viewer; the green and blue double-arrows show how any angle away from perpendicular will shorten the apparent length of the bill.

Finally consider that we don't know the actual length of the bill - Johnson and Johnson used the average bill length for each taxa, but I doubt that there is a significant correlation between bill length and PE. There is a 7.4mm spread for the bill length of fulva, and a 3.7mm spread for dominica - I am sure the latter would have been greater had the sample size (45) been closer to that for fulva (441).

When you consider all of the above elements and variables, it seems clear that assessment of PE based on a comparison to bill length on live birds in the field can only provide a "broad-brush" value at best - not one that can be accurately stated in millimeters.

My second concern is to the precision of the stated data. Keep in mind that the shortest measured Golden-Plover bill is c. 20mm, and changes in angle-of-view can only make the bill look shorter, not longer. Thus when assessing PE, if it looks to be more than half the length of the bill, it must be more than 10mm; if it looks to be 2/3rds of the bill, it must be at least 16mm, and so on. Similarly if the PE looks to be less than a quarter of the bill length, then (using a maximum measured length of almost 28mm) is must be less than 7mm, and so on. That is about all we can determine about the actual length of the PE.

The next question is: how accurate is the 9-10mm break point? - not very, I'd suggest. Actually to be fair, it may be a one-way feature, in that I've yet to document a definite dominica that has a PE obviously less than half the bill length - but I feel that there are many examples of fulva with a PE clearly more than half the bill length.

CLICK HERE to see one of the shorter-winged presumed dominica I've photographed; the PE is - give or take a mm due the the imprecision of measuring this value - half the apparent bill length, so based on the average for dominica (22.8) this makes it in the 11-12m range; based on the full dominica spread it is between 10.5 and 12.4mm.

CLICK HERE to see a bird that - if a dominica - shatters the established break point. Sadly I don't have any images of the whole bird at just the right angle and posture, so I used two separate images digiscoped at the same magnification; the PE is - give or take a mm due the the imprecision of measuring this value - between a quarter and a fifth of the apparent bill length (also the bill is clearly foreshortened in the comparative image), so based on the average for dominica (22.8) this makes it in the 4 - 5mm range; based on the full dominica spread it is between 4 and 6mm.

If it's a fulva (a classic fulva was documented in the same Golden Plover mega-flock the same day) it would make it in the 5 -6mm range; based on the full fulva spread it is between 4 and 7mm. Other elements suggest an ID of fulva for this individual: long tertials plus short primary projection, with only 3 visible P-tips - that last two very close together; a buffy wash to parts of the head.

Examples of fulva with PE more than half the bill length; these are all from eastern Australia in Jan - Mar, by Laurie Knight:

below, the rearmost bird:

Fore more examples of long-winged fulva, CLICK HERE to visit on old (2001) page I set up on the subject.

IN SUMMARY: A Golden Plover with a Primary Extension (PE) clearly less than half the bill length should be a fulva, assuming there are no other contradictory features. A Golden Plover with a PE equal to or greater than the bill length should be a dominica, assuming there are no other contradictory features. Golden Plovers in-between these PE values could be either taxon, and will require careful assessment of other features - in the end some with contradictory features may be unidentifiable, and some could be hybrids.

|

Martin Reid

Ocotber 2011.